History of Chinese Writing: From Oracle Bones to Today's Characters

Chinese writing is one of the oldest continuous writing systems in the world. Its earliest clear evidence comes from oracle bones used by the Shang rulers around 1600–1046 BC. Those inscriptions were carved on turtle shells and ox bones for divination, recording questions to ancestors and kings' actions. That simple fact explains why Chinese characters began as practical marks tied to ritual and state needs.

Origins and major early scripts

Oracle bone script shows signs of pictographs and simple ideographs, where a shape stands for an object or idea. As metalworking rose, inscriptions moved onto bronze vessels with more stylized forms called bronze script. Later, during the late Zhou and Qin periods, scripts became more uniform. The Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) pushed a standardized small seal script to help administration across a newly unified state. Standardization made writing useful for law, tax records, and communication across dialects.

Characters are mostly logographs: many stand for words or morphemes rather than single sounds. Over time scribes developed components and rules. A common pattern pairs a semantic part that hints at meaning with a phonetic part that hints at sound. That mix helped readers guess meanings or pronunciations even when a full spelling system did not exist.

From clerical hands to modern forms

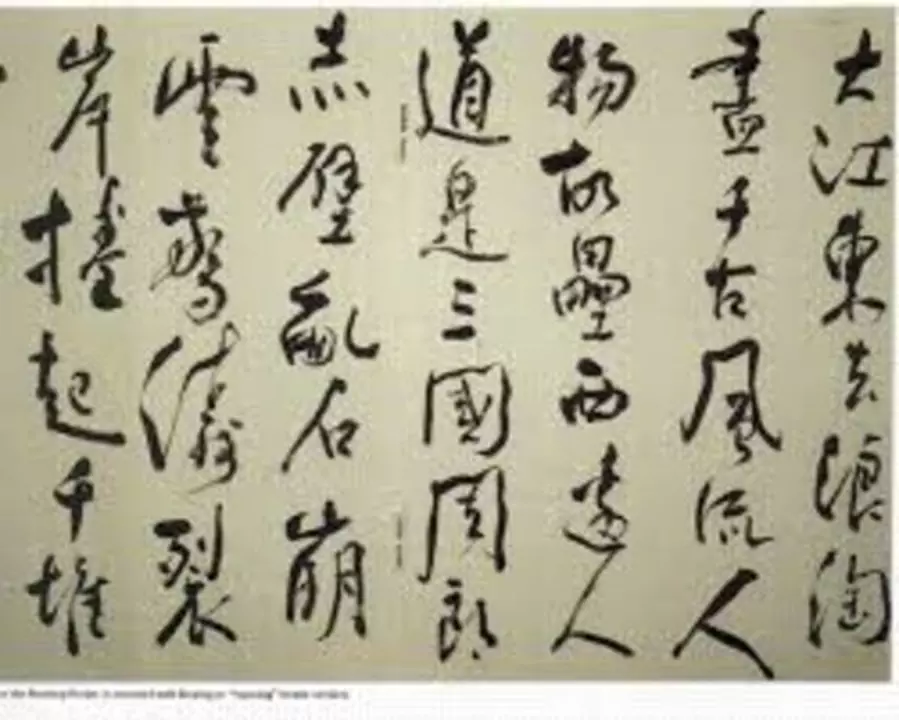

In the Han dynasty scribes simplified the seal shapes into the clerical script to write faster on paper and bamboo. Clerical script introduced flatter, straighter strokes and set the stage for regular script (kaishu), which became dominant from the third to seventh centuries and remains the standard style for printed text. Cursive and semi-cursive styles developed for speed and personal expression; you still see those in calligraphy today.

Through centuries the set of common characters expanded and stabilized. Officials compiled dictionaries and lists of radicals—basic components used to organize characters in reference works. That system helps learners look up unknown signs even now. By the 20th century, different regions chose different reforms: mainland China adopted simplified characters to raise literacy, while Taiwan, Hong Kong, and many overseas communities keep traditional forms.

Chinese writing influenced neighbors: Japan adapted characters as kanji, Korea used hanja historically, and Vietnam once used chu nom. Today most users type characters with phonetic input like pinyin, or by shape-based systems on phones and computers. The writing's long history gives it continuity and flexibility: old inscriptions let scholars trace change, while modern tools make characters practical for daily use. Curious how a 3,000-year-old system still fits smartphones? That tension is part of why Chinese writing stays interesting and widely studied.

Archaeological sites like Anyang in Henan province produced thousands of oracle bone fragments that let historians date early characters precisely. If you're learning Chinese, start with high-frequency characters and learn common radicals such as water (氵) or person (亻). Recognizing radicals speeds up memorization and helps with dictionaries. Also try writing by hand; muscle memory builds recognition faster than typing alone. Small daily practice beats occasional long sessions.

Where did the Chinese system of writing come from?

The Chinese system of writing is one of the oldest writing systems known to man, with roots going back to the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC). It is a logographic writing system, meaning that each character represents a word or an idea, rather than a single sound. This system of writing has been passed down through generations and is still in use today. It is considered one of the most complex writing systems in history and is composed of thousands of characters. Chinese writing has had a profound influence on other writing systems in East Asia, and its influence continues to be felt in modern times.